Playable English Localizations of Slovak Digital Games From the Late 80s Period (updated)

English translations of early Slovak digital games from the late 80s period, created in cooperation with Slovak Game Developers Association by Stanislav Hrda, Slavomír Labský, Marián Kabát, Darren Chastney, Jakub Celušák and Maroš Brojo.

Download games

ENG versions of all games

Accompanying content

Guides for all games

Maps for all games

Emulator

Fuse emulator

List of translated games

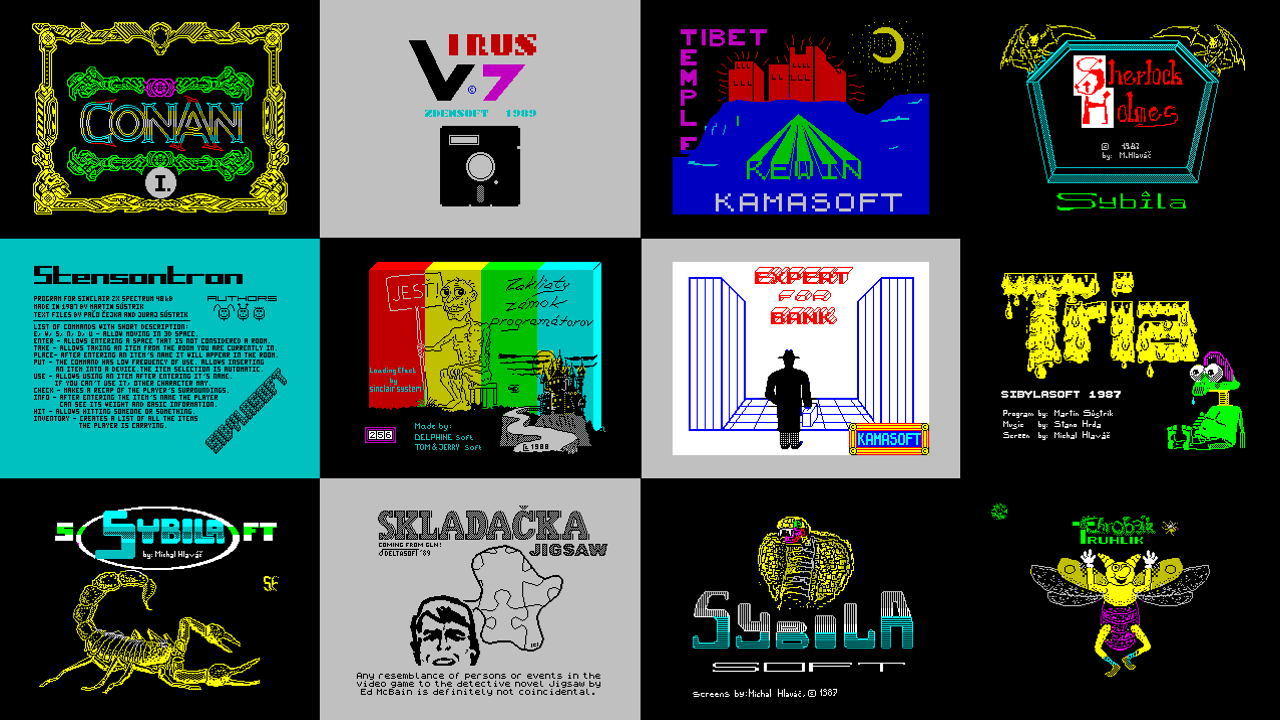

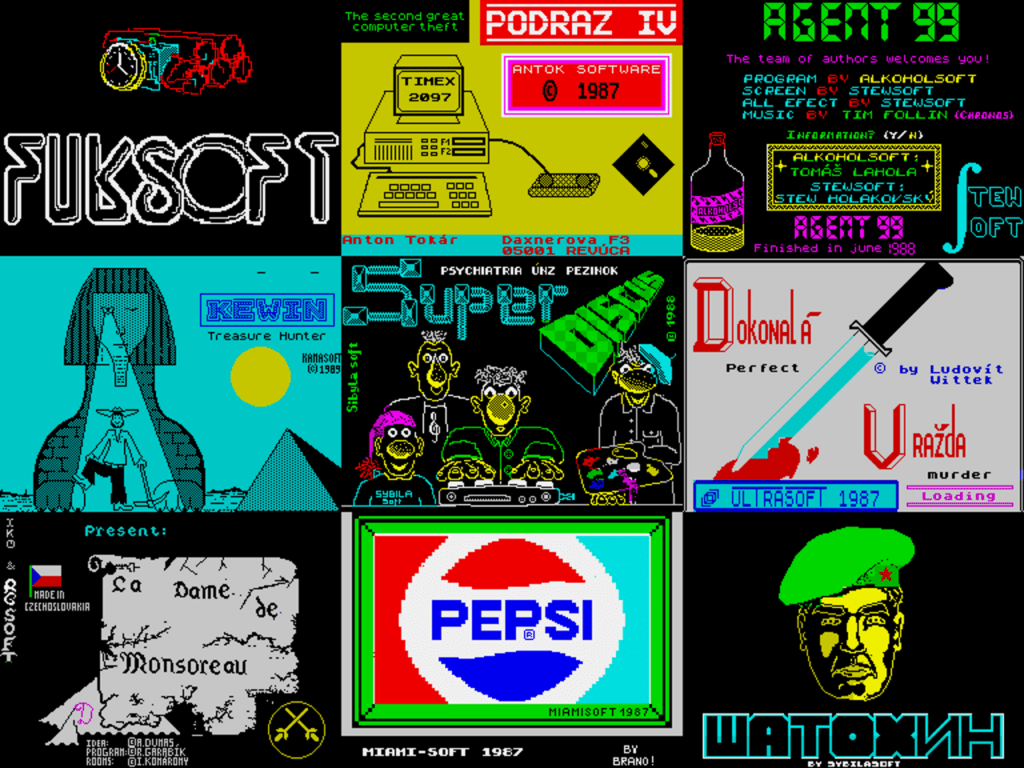

Stensonstron (1987, Sybilasoft)

Sherlock Holmes and the Three Garridebs (1987, Sybilasoft)

Plutonia (1987, Sybilasoft)

Tria (1987, Sybilasoft)

Fuksoft (1987, Sybilasoft)

La Dame de Monsoreau (1987, IKO a RGSoft)

Perfect Murder (1987, Ultrasoft)

Pepsi Cola (1987, Miami-Soft)

Super Discus (1987, Sibylasoft)

The Stig 4 (1987, Antok Software)

Agent 99 (1988, Alkoholsoft)

Prípad 2 (1988, Shrap Software)

Programmers‘ Cursed Castle (1988, Tom & Jerry Soft)

Perfect Murder 2: Bukapao (1988, Ultrasoft)

Satochin (1988, Sybilasoft)

Kewin 1 (1988, Kamasoft)

Expert for bank (1988, Kamasoft)

P.R.E.S.T.A.V.B.A. (1988, Cybexlab) – bonus

Kewin 2 (1989, Kamasoft)

Jigsaw (1989, Deltasoft)

Revenge (1989, DDsoft)

Virus 7 (1989, Zdensoft)

Pouch the Beetle (1991, Sybilasoft)

Conan I (1991, Golden Circle)

More information on Slovak games history

www.scd.sk/hry

Credits

Translation project created by Slovak Game Developers Association in cooperation with Slovak Design Museum

Localization lead: Marián Kabát

Proofreading: Darren Chastney

Documentation: Stanislav Hrda (Sybilasoft)

Restoration: Slavo Labský (Busy soft)

Mapping, guides: Jakub Celušák

Coordination: Maroš Brojo

Translations: Mária Koscelníková, Linda Janíková, Milan Velecký, Alex Barák, Matúš Nemergut, Katarína Bodišová

Supported using public funding by Slovak Arts Council

Contact

Maroš Brojo

Translation project coordinator

maros.brojo@sgda.sk

Stanislav Hrda (Sybilasoft)

Support for games

stano.hrda@gmail.com

Slovak digital games translation project introduction

Maroš Brojo

Multimedia curator at the Slovak Design Museum

The history of digital games in Slovakia dates to the first half of the 1980s. Its beginnings are mainly associated with amateur and semi-professional development, whose emergence and formation in that period was conditioned mainly (but not only) by the popularity and spread of the ZX Spectrum computer and its first clones in Czechoslovakia, such as Didaktik Gama or Didaktik M from the Didaktik Skalica factory.

It was at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s that the first generation of creators, influenced by commercial game development from Western Europe or the United States, was formed in our country. Several local communities were gradually formed around the phenomenon of video game creation all over Slovakia. There was an active exchange and copying of games on cassettes in Svazarm’s interest groups, fans of personal computers exchanged their experiences, and many of them, following the example of the West, began to create their own games, which were shared among friends and acquaintances all over Czechoslovakia.

Today, we consider games from this period to be a key part of the history of home production, which, like other historical works, belongs to our cultural heritage. Historical and theoretical research on digital games, to which entire university departments are devoted and which is considered a regular part of academic research by several experts around the world, has been going on for a long time without the rest of the world having the opportunity to get acquainted with our national production.

Indeed, a huge problem in this area is the fact that the vast majority of our games from this period were created in the Slovak language. Games produced in this way are thus inaccessible and unplayable for foreign researchers working on the history of national productions, larger geographic regions, or specific game genres across different countries. The problem is particularly acute for the text adventure genre, built primarily on interactive text rather than the graphics and action of contemporary games.

Information-laden text adventure games, which often touched on various socio-cultural phenomena in our territory or even reflected on the previous regime, can thus only be described by researchers from the indirect narratives of the Slovaks who played them. Translations of these games would allow a wider professional and academic public worldwide direct contact with our gaming history and would bring greater visibility for it worldwide.

The project of translating Slovak games from the 80s and 90s aims to start a gradual translation of the most important early games from this period, doing such translation directly at the level of the original software, so that the games are runnable (for historical accuracy) on 8-bit computers from that period. At the same time, users of modern computers will be able to run the games on modern hardware thanks to emulators. With the permission of the authors already secured, we plan to gradually translate and make available to the public 10 selected major text adventure games in the first year, and at least 10 to 20 other works from the period in the following years.

Professionals from two fields are involved in the project and are key to its realization:

1) translation studies

2) programming + knowledge of historical works

For the first area, we worked with a trained translator and translation coordinator who had pre-existing experience in localizing video games, Mgr. Marián Kabát, PhD, a graduate of translation studies at Comenius University. For the second area, we collaborated with original creators of games from this period, who also do programming as part of their profession and who participated in the technical component of the project (text extraction and implementation of translations into the games). Mgr. Stanislav Hrda, a graduate of theoretical computer science at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics of Comenius University, currently works as a sales consultant at the distributor of Cisco network elements, game creator and member of the then Sybilasoft group, and Ing. Slavomír Labský, a graduate of IT at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering of the Slovak Technical University, a leading personality of the Slovak demoscene, author of games from that period, currently works for Eset as a digital infiltration analyst. Stanislav Hrda is, among other titles, the author of the game Šatochín (1988), whose sample partial translation we used at the beginning of the project to verify and demonstrate its feasibility. Project coordination and promotion is provided by Mgr. Art. Maroš Brojo, a graduate of Audiovisual Studies at the Film and TV Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts, who works at the Slovak Game Developers Association as a general manager and at the Slovak Design Museum as a curator of the multimedia collection, where he is also engaged in historical research of contemporary Slovak computer games.

The games translated over the next 2-3 years after the end of the project will represent almost the complete video game production from the period of 8-bit computers in Slovakia, with an emphasis on text adventure games. All translated games are, with the permission of the authors, freely distributable for research and non-commercial purposes.

Due to the way the video games have been translated, they are playable via media such as floppy disks, cassettes, and memory cards even on the original hardware, making it possible to achieve almost complete historical accuracy when playing them. For convenience, however, they can also be played on well-known emulators such as Speccy or ZX Spectrum 4. On behalf of the entire team, we firmly believe that the translated games will bring you an enriching insight into the video game history of Slovak creators in Czechoslovakia and reveal a hitherto unexplored branch of the local history of the now dominant and globally widespread medium.

How were games created in the countries behind the Iron Curtain?

Stanislav Hrda

Game developer

Microcomputers came into homes in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It was no different in the countries behind the Iron Curtain, often referred to as Soviet satellites. Typical of these countries was that microcomputers were quite difficult for people to obtain, so they smuggled them in from the West, since domestic production of computers was either non-existent or involved relatively underdeveloped computers with inferior specs, which was, of course, quite a handicap for gaming.

The videogame enthusiasm mainly affected children and teenagers, who in countries with non-existent copyright protection were copying games from the West and playing them at home or even in existing computer clubs. The more skillful ones went from playing games to trying to create them. However, the games were not sold in shops and the authors were not entitled to remuneration. Therefore, practically no one could engage in video game programming as a business activity, and adult programmers worked at most in state institutions on large mainframe computers. Thus, video game programmers became mainly teenagers. The possibilities were limited; not many people at that age could create truly perfect games with nice video game graphics, but without a financial reward.

Text adventure games became a very popular domain. These could also be programmed in the simpler Basic language that every home computer had built in. Text-based games offered the opportunity to imprint one’s fantasies into a world of characters, locations, descriptions of reality or fantasy at will. That is why hundreds of such video games were created in the 1980s in Czechoslovakia. The authors from the ranks of teenagers portrayed their friends, but also heroes from films that were distributed on VHS tapes or from the pop-cultural world of the West from the occasionally available comics, films, TV series and books.

Some wrote their own science fiction or fantasy stories in the text games, others mixed reality with a pop-cultural mix of references to things and realities that interested and fascinated the author or were the subject of discussion among the authors‘ friends. A separate chapter was the games labelled as subversive towards the communist regime. Where the authors invited people to an anti-regime unauthorized demonstration or described the frequent dream of escaping to the West. For example, in the video game P.Ř.E.S.T.A.V.B.A. (ÚV Software, Jaroslav Fídler, 1988) you blow up a statue of V. I. Lenin, the founder of Soviet communism, with dynamite, and under the statue you find a gold brick that allows you to emigrate to the free West.

In another such game, Šatochín (Sybilasoft, Stanislav Hrda, 1988), the archetype of the American invincible superhero Rambo competes with his Soviet counterpart, Major Šatochín, on the battlefield in Vietnam. Let us add that, of course, the mention of Rambo was unimaginable in the official media, newspapers, or books under the control of censorship. But for the aging gerontocracy of the communist kleptocracy, the field of video games and the subgenre of home-made text adventure games were under the radar, and the games circulated freely, mainly among friends, without restriction or censorship, as with inconvenient books by inconvenient authors.

Therefore, it was possible for authors to sneak in such symbols and entertain their fellow gamers with their bravery. Decades later, we are trying to translate this peculiar world of text adventure games from the then East into English to get them into the hands of the global community of gamers. Firstly, perhaps as a curiosity for the retro scene, study material for sociologists on the emergence of games in non-standard conditions, or historians charting the narrative of the freer media that text games were in the more difficult conditions of less free countries. Wherever you are from, we will eventually come to the conclusion that no matter where you come from, the phenomenon of video or computer games has engulfed a generation of children and teenagers at a rapid pace since the memorable 1980s.

And even with these hitherto unknown games, the common thread holds true – they were created to entertain the creators, their friends, the gaming community, and regardless of genre or thematic content, it was always about making the game playable and entertaining in the first place. And that’s more or less what the authors from this corner of the world have managed to create. Even though they may seem strange to you today and many of the period contexts won’t be entirely obvious. But you’ll certainly get the urge to play with some of the more intricate titles. And the surprising and perhaps even obscure themes of these games can still be an enrichment to the gaming scene today, for example in exploring how far the boundaries of game design can go.

Localizing Slovak text adventures

Marián Kabát

Translations coordinator

At the beginning of 2021 I was approached by Maroš Brojo from the SGDA association who asked me if I would like to participate in a project to translate historically significant Slovak video games into English. Since I am involved in software localization theoretically at the Faculty of Arts of Comenius University in Bratislava, but also practically as a freelance translator, I couldn’t help but agree.

The project team (Maroš Brojo, Stanislav Hrda, Slavomír Labský and I) selected 10 historically significant text adventures by different authors. At the same time, I assembled a team of five translators who divided the games and worked on the translation:

Mária Koscelníkova – Super Discus, Fuksoft, Virus 7, Jigsaw

Linda Janíková – Satochin, Perfect Murder, Stensontron, Sherlock Holmes and the Three Garridebs

Milan Velecký – Betrayal 4, La Dame de Monsoreau, Pouch the Beetle, Conan I

Alex Barák – Agent 99, Pepsi Cola, Tria, Programmers‘ Cursed Castle, Plutonia

Matúš Nemergut – Perfect Murder 2, Kewin 2, Prípad 2, Kewin 1

Katarína Bodišová – Expert for Bank, Revenge

My job was to supervise the translations, reconcile any differences and advise if the translators got stuck on something.

As these were first-generation Slovak games, we assumed that in translation we would encounter realia or expressions that might not be familiar to today’s player, either because of time or geographical differences. I will give at least a few illustrative examples for all of them.

The very first game we worked on, Šatochín, mentioned „babeta“ in the environment descriptions, but since it is a Czechoslovak brand of moped, we had to replace it with a name that would be familiar to an English-speaking audience. We decided to use the name „JAWA“, by which a “babeta” is known abroad.

The game Fuksoft referred to the singers J. Nohavica and V. Vysotsky. These names could not be directly substituted because they completed the cultural context of the game, so we had to add an explanation to the translation that they were folk singers.

We also added context in the game La Dame de Monsoreau, the introduction of which mentions the first edition of the book The Lady of Monsoreau in Slovak. In the English translation of the game, the player finds out about the first English edition as well.

However, such additions to the text were difficult due to the technical aspect of the games – the lengths of the individual text segments were fixed, and we were not allowed to exceed them in translation, so we often had to abbreviate the texts by using abbreviations (instead of „you“ we sometimes used the colloquial „u“). In other cases, the truncation was avoided – the word „south“ is 2 characters longer than the original „juh“, fortunately this problem could be handled programmatically, so the player will see the full word instead of the abbreviation „S“.

Finally, we also had to work around allusions that might sound vulgar or politically incorrect from today’s point of view. There are three characters in Kewin 2, and each has a different face color. To avoid politically incorrect naming, we have reworked the translation to imply that the characters had their faces painted.

I could list many more similar and different examples. However, I must conclude that both from a scholarly and practical point of view, this project has been a great challenge, and one that I hope will bear fruit – whether in the form of further research in the fields of video game design, history and localization, or as an opportunity to explore new cultural environments and new gaming experiences.

Specifics of porting historical video games for the ZX Spectrum platform into English

Slavomír Labský a.k.a. Busy

Programmer

At the beginning of 2021, my friend Maroš Brojo approached me with an interesting project – to port several historical Slovak text games for the ZX Spectrum into English, so that our Spectrum brothers outside Czechoslovakia could play them as well. And most importantly, to show what games were made behind the Iron Curtain during our much (un)loved totalitarian regime.

I liked this idea, so I agreed to participate in the project. I was also very happy to join the project because some of the games were made by the well-known company SYBILASOFT and Stano Hrda, probably the most famous member of this company and my friend, also collaborated on the project.

My task was to literally „hack“ the selected games – to disassemble them, find and remove all the original Slovak texts, then insert new English ones instead and put the games back together in a functional state. Since I already have a lot of experience with hacking programs (e.g., finding and creating cheats for games – infinite lives, infinite energy, etc.) and moreover I have done similar disassembling and reassembling for Ultrasoft before, where I remade games on cassette and floppy disks with copy-protection. Therefore, I was literally looking forward to the task. 🙂

Hacking or disassembling most games was very easy. All I had to do was let the game load into memory and then save the memory image to a file. And figure out where and how the game boots up, so I could then put it back together later. It was a bit harder with games equipped with various exotic tape loaders with non-standard loading, which didn’t work well enough on modern media anymore. But in such cases I usually just had to do a bit of googling and find a different version of that game with a differently modified loading (apparently sometimes it couldn’t be loaded even in the distant past 🙂 ) and that modified version worked nicely for me.

Once I had a memory image of the game prepared and saved, the next task appeared in front of me – how to extract all the texts from it. As a man abounding in laziness, I certainly didn’t feel like manually searching and copying out the texts. So I programmed my own program for this purpose, which goes through the stored memory image and searches for the texts. Programming your own utility to search for texts may sound easy, but when you get down to it, you’ll find that it’s not so easy after all. The problem is that a lot of the text in the game isn’t actual text – it could be some graphic or code that happened to hit the text encoding. So I’ve had to add various sophisticated criteria to the program – for example, that the text must be multiple letters together, that the text must be in quotes, or what other characters (!@#$%^&*….) can still be part of regular text.

Some games used various special formatting characters, such as the [ character to wrap text to a new line, or the abbreviation #X where X is the number of spaces typed. The program also had to accept these special characters and treat them as text, so that its output would be complete sentences, which after all can be translated better and more accurately than single isolated words.

I still always went through all the texts found by the program in this way manually, just to be sure, because despite the sophisticated criteria, here and there among the required texts there was something that was not text to be translated. For example, long descriptive variable names in Basic – the player does not see these when playing, so they definitely do not need to be translated. 🙂 Or another example – some games had texts stored in the classic Pascal way – the length of the text was stored in memory first, followed by the text itself without any termination (which is not needed, since its length is known). Occasionally it happened that the length of the text was just a value that hit the code of a letter, and the program then thought that this letter should also be part of the text.

Later, when I received the translated English texts, the second, perhaps even more difficult part of the job began. Since I am (as I mentioned) a lazy person and didn’t want to search for the original Slovak texts manually, I didn’t want to manually insert the new English texts back into the game either, of course. So I made a program for this purpose too (and the computer did all the pasting, hehe 🙂 ). Occasionally it happened that the English-translated text was longer than the original Slovak one and contained some characters outside the standard ASCII set (especially Unicode characters, which ZX Spectrum never dreamed of even in its wildest dreams). To prevent hieroglyphics from appearing instead of the new English text, or longer text from overwriting some other part of the game, I equipped the embedding program with checking mechanisms that always alerted me to a possible problem with the text. I also corrected invalid characters myself, but when the text was longer, the translators had to come up with something shorter and more concise that fit the context.

They had to, but it didn’t always work. For example, the original Slovak text was JUH, and the English should be SOUTH. But in English the text is longer, and a shorter equivalent simply doesn’t exist (unless we want to use the letters themselves, which we don’t). Fortunately, in this case, wherever there was JUH, there was also SEVER, VÝCHOD and ZÁPAD somewhere nearby. When I used NORTH, EAST, WEST respectively instead, I spared two letters, and shuffled the game’s code so that just those two vacant letters were filled by the longer SOUTH. And that’s it, as certain two famous Czech fairy tale characters would say. 🙂

Once the English texts were implemented into the game, the last task before me was to put the game back together so that it would work. I had to figure out where the game launches and what it needed to have in memory to run properly. This is where the information I had gathered at the beginning when taking the game apart usually helped me. Sometimes it was necessary to write completely new startup code and paste it into the game so that it would run correctly.

In the past, I was quite annoyed to hear large areas of memory being unused during a long 5-minute tape loading of a game – all older spectrum players are very familiar with the long monotonous whistle of all zero bytes. 🙂 I was therefore very happy when the program was packed – instead of 5 minutes, it was loaded in say only 2 minutes and no annoying monotonous beeping took place. So I decided to use this for the games I was now editing, and pack the games as well. I know, in these days of modern fast and large capacity media, it doesn’t make any practical sense anymore. It doesn’t matter if a game loads in one or two seconds, and it also doesn’t matter if a game takes up 20 or 40 KB on a terabyte disk. But I’m just old school and it didn’t work for me. I like the game file to be as short as possible, the information in it to be stored efficiently, and there are no unnecessary large unused areas. I used my other program, LzxPack, to do the packing. The program uses optimal LZ compression, which achieves very good compression ratios, and unpacking the game after it is loaded into the ZX Spectrum is practically instantaneous (a few seconds max), so it doesn’t even delay the user too much before playing.

I mentioned above that some versions of games used a special tape loader, which while interesting from a historical perspective (e.g., showing a counter of how much more the game has to load), is unfortunately not compatible with today’s modern fast media. So I decided to remove such loaders from games and make a simple basic loader for all games that work directly and seamlessly everywhere – both in all ZX Spectrum emulators and in all modern storage devices (MB02, MB03, divide, divmmc…). At the same time, it can be adapted very easily and seamlessly to any older floppy drives that were once used on the ZX Spectrum and quite a few people still own (D40/D80, +D/Disciple, Betadisk, Microdrive…). And, of course, the oldest storage medium – magnetic tape – still works if anyone would like to use it. 🙂 Thanks to this, anyone can play the games – either on an emulator or on a real physical ZX Spectrum.

Supported using public funding by Slovak Arts Council